| Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, ISSN 1923-2861 print, 1923-287X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Endocrinol Metab and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jofem.org |

Letter to the Editor

Volume 1, Number 4, October 2011, pages 201-203

Which Is the Best Treatment for Diabetes Complicated With Severe Obesity, Intensive Insulin Therapy or Basal Supported Oral Therapy or Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Analog?

Sumie Moriyamaa, c, Hidekatsu Yanaia, b, c, d

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Kohnodai Hospital, Ichikawa, Japan

bClinical Research Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Kohnodai Hospital, Ichikawa, Japan

cSumie Moriyama and Hidekatsu Yanai contributed equally to this study

dCorresponding author: Hidekatsu Yanai. E-mail:

Manuscript accepted for publication October 12, 2011

Short title: Letter to the Editor

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jem50w

| To the Editor | ▴Top |

Type 2 diabetes is commonly complicated with obesity. Although achieving a healthy weight and preventing weight gain are integral components of optimal diabetes management, an improvement of glycemic control with the treatment usually induces weight gain [1]. Until now, we do not exactly understand which treatment is the best for diabetes complicated with severe obesity. We will show the changes in body weight and glycemic control in a type 2 diabetic patient complicated with severe obesity, by the intensive insulin therapy (IIT), basal supported oral therapy (BOT), and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog.

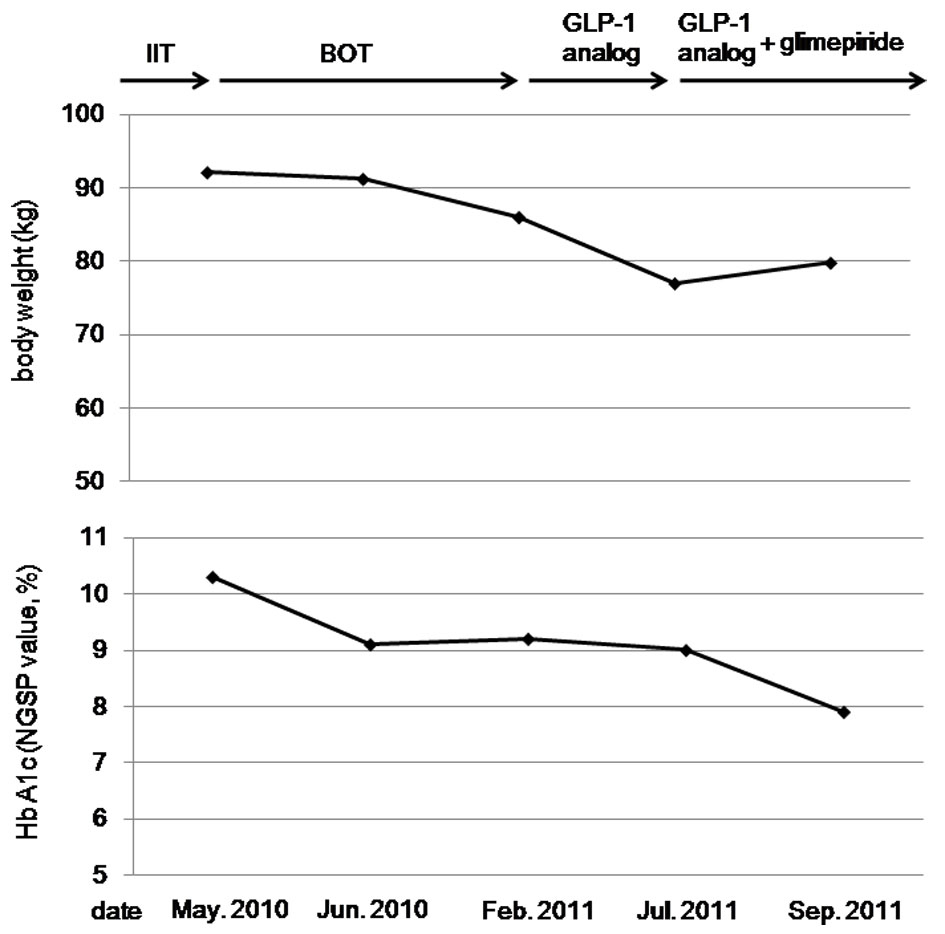

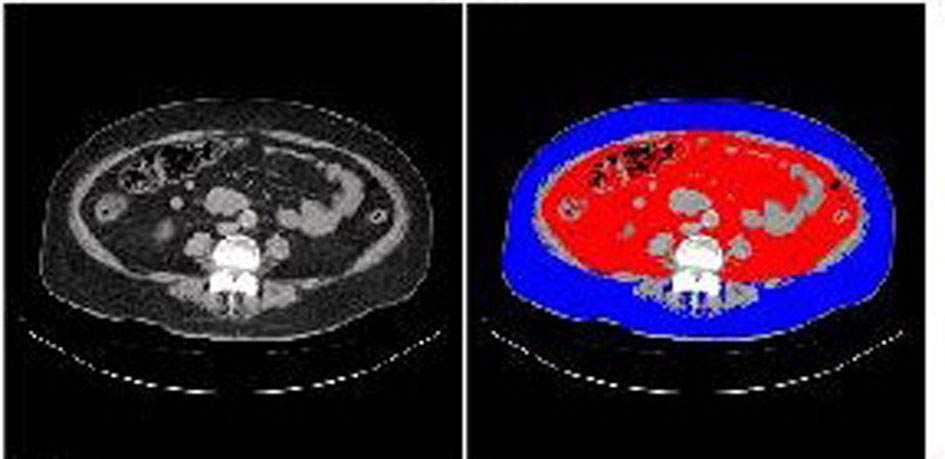

A 60-year-old woman was referred and admitted to our hospital due to poor blood glucose control in spite of the treatment by IIT. At the age of 47 she was diagnosed as type 2 diabetes. For the last one year, she was treated with four daily insulin injections: three injections of insulin aspart before breakfast (14 units), lunch (14 units), and dinner (14 units) and one of insulin detemir (18 units) at bedtime. Her body weight was 92.1 kg and height 149 cm (BMI 41.5 kg/m2). Fasting plasma glucose (284 mg/dl) and HbA1c (NGSP value, 10.3%) levels were significantly elevated. Switching from IIT to BOT (glimepiride 1 mg/day, metformin 1,000 mg/day, and insulin glargine 24 units/day) reduced body weight (from 92.1 to 86.0 kg) andHbA1c (from 10.3 to 9.2%) after 9 months (Fig. 1). However, we decided to change the treatment from BOT to the GLP-1 analog (liraglutide) use, because her HbA1c level was still high. At this time, her body weight was 86 kg and height 149 cm (BMI 38.7 kg/m2). As a result of the measurement using abdominal computed tomography, abdominal circumference was 121.0 cm, while subcutaneous fat area and visceral fat area were 374.5 and 362.6 cm2 (Fig. 2), respectively, showing severe obesity. To understand her insulin-dependence, a glucagon loading test and the measurement of daily urinary C-peptide (CPR) level were performed. Serum fasting CPR level and serum CPR level at 6 minutes after a glucagon loading were 1.28 and 3.31 ng/ml, respectively, and urinary CPR level was 40.6 µg/day, which indicated that she has a sufficient insulin secretion capacity. Therefore, we switched from BOT to the GLP-1 analog use. Switching to the GLP-1 analog (liraglutide 0.9 mg/day) as monotherapy significantly reduced body weight (from 86.0 to 77.0 kg) after five months, and the addition of daily 1 mg of glimepiride to the GLP-1 analog significantly reduced HbA1c (from 9.0 to 7.9%) (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. The changes in body weight and HbA1c levels by the intensive insulin therapy (IIT), the basal supported oral therapy (BOT), and the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Abdominal computed tomography. Red and blue areas indicate visceral fat and subcutaneous fat area, respectively. |

Therapeutic strategies to prevent or minimize weight gain, especially in obese diabetic patients, are very important to help diabetic patients manage their glycemic control and keep or improve their quality of life. However, an intensive therapy is likely to induce weight gain. Weight gain was identified as a sequela of IIT in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), which is a multicenter controlled clinical trial designated to determine the effects of two different diabetes treatment regimens on complications of type 1 diabetic patients [2]. Higher baseline HbA1c levels and greater decrements in HbA1c during intensive therapy were both associated with greater weight gain in the DCCT. In our patients, switching from IIT to BOT decreased daily insulin use from 60 units to 24 units, which may be associated with weight loss. BOT has been reported to minimize weight gain compared with premixed insulin and prandial insulin regimens [1], supporting our result.

The effects of liraglutide have been studied in the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes (LEAD). In the LEAD-5 study, liraglutide added to metformin and sulfonylurea produced significant improvements in glycemic control and body weight compared with placebo and insulin glargine [3]. In our patient, switching from BOT using insulin glargine to the GLP-1 analog use significantly reduced body weight and HbA1c level, showing an agreement with the result of LEAD-5 study. GLP-1 is released into the blood from intestinal L-cells in response to meal ingestion. GLP-1 stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic ß-cells in a glucose-dependent manner, and slows gastric emptying, which may aid weight loss and resulting amelioration in glycemic control [4].

In conclusion, the GLP-1 analog use may be an excellent therapeutic strategy for the diabetes management of type 2 diabetic patients who have sufficient insulin secretion capacity, complicated with severe obesity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Grant of National Center for Global Health and Medicine (22-120).

| References | ▴Top |

- Davies M, Khunti K. Insulin management in overweight or obese type 2 diabetes patients: the role of insulin glargine. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10 Suppl 2 :42-49.

pubmed - Weight gain associated with intensive therapy in the diabetes control and complications trial. The DCCT Research Group. Diabetes Care. 1988;11(7):567-573.

pubmed doi - Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, Sethi BK, Lalic N, Antic S, Zdravkovic M, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met+SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52(10):2046-2055.

pubmed doi - Kjems LL, Holst JJ, Volund A, Madsbad S. The influence of GLP-1 on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: effects on beta-cell sensitivity in type 2 and nondiabetic subjects.Diabetes. 2003;52(2):380-386.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism is published by Elmer Press Inc.